What is it about ideological free marketeers and their shaky relationship with the facts? Everyone likes markets and free exchange is one of the best manifestations of human co-operation there is – so why tell lies about their limitations and the infrastructure required to make them work for our benefit?

Sam Bowman of the Adam Smith Institute is keen to adapt the often pejorative label of ‘neoliberalism’ to his cheery brand of paid-for market propaganda, and promotes it under this banner in an article in the online i newspaper. He defines a neoliberal as

someone who thinks that lightly-regulated markets, free trade and free movement are the best way to create wealth and innovation domestically and globally, but that the state does have a role to play in redistributing some of the proceeds to the least well-off.

Essentially this could equally be described as market-friendly social democracy – it’s a question of how light the regulation and how big a role there is for redistribution. And as such these approaches share the same shortcoming. The power of market actors eventually overwhelms the power of states to regulate and redistribute.

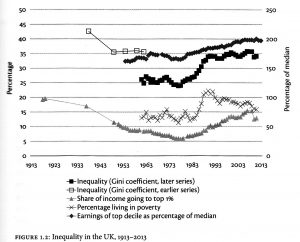

It is good that Sam welcomes the fall in extreme global poverty – it would be truly shocking if we had not met success in tackling this – but a massive contribution has been made by China which, while it has made pragmatic use of trade and markets, frankly cannot be described as liberal, neo or otherwise. He goes on to make the almost certainly incorrect claim that ‘inequality in Britain is now at its lowest point since 1985’. The chart below from the late Anthony Atkinson’s Inequality shows a variety of indicators, which all confirm that inequality, while it has fallen slightly since the financial crisis, remains high relative to the early 1980s, before Margaret Thatcher’s peak neoliberalism took hold.

Bowman also makes the claim that ‘wages for the bottom 20% have risen by 13% in real terms since the crisis’. This is a misrepresentation that proves almost exactly the opposite of his case. It is true that household disposable income of those who are at the top of the lowest 20% (those on the 20th percentile) have increased by this percentage since 2007, but this takes into account pensions, benefits and tax credits, as well as the introduction of the national living wage (NLW) in 2015. If we look at rewards from employment, or wages as Bowman refers to, a completely different picture emerges. Despite the NLW the 20th percentile have seen their gross weekly earnings from employment fall by 2.4% since 2007, while the median group or 50th percentile (those exactly midway between the bottom and top half of the earnings distribution) have seen them fall by 4.4%. (See the chart below.) In other words, it has required state intervention to counter the poor performance of the UK’s ‘neoliberal’ economy and to provide decent incomes.

If neo-liberalism has held sway in Britain over the last 10 years it has delivered low productivity and low real wages. This demonstrates that current market outcomes are frequently undesirable and require state intervention to render socially acceptable results. Markets are a weapon against poverty and for prosperity – but they are not a system – the system we need is democracy and we need it to extend more deeply into economic life.