Introduction

Just how much cash does the NHS and social care need to prevent the distressing stories of patients languishing on trolleys for hours in A&E departments? Can we possibly afford what it needs, or is it really a ‘bottomless pit’ as often claimed? Do we need to lower our expectations of what can be provided for us? Or does the whole funding system of the NHS need to be overhauled, with charges and/or insurance-style payments? Sadly, we are frequently being directed by politicians’ state-shrinking agendas and commentators’ ignorance towards the wrong numbers and the wrong reading of those numbers, with the result that the wrong answers are given to these questions. The truth is that if we look at things correctly, there is no reason why we cannot have an excellent healthcare system in Britain without any great sacrifice in our enjoyment of the other goods and services that the modern economy has to offer.

Accounting for Healthcare

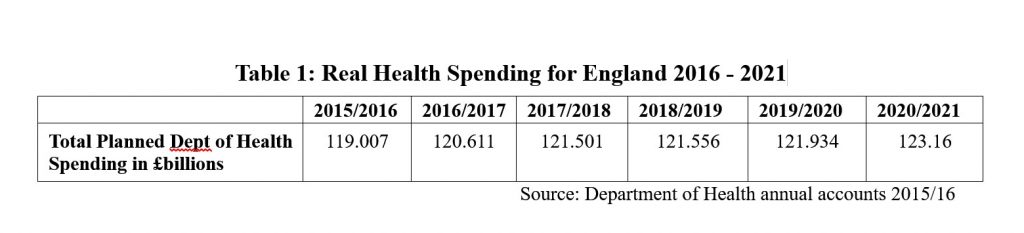

How should we assess our spending on health and care? We could assume that everything else stands still – money does not lose value because of inflation and the economy does not grow bigger over time as our population and productivity grows. Here we just simply look at the amount of cash the government spends each year. This number has grown massively since 1970 and continues to do so. It should be obvious that inflation needs to be taken into account if we are to make proper comparisons from year to year, so more usually when spending is stated this is done so in ‘real’ terms, meaning that the cash sums are adjusted for the average prices of goods and services expected in each year to which they refer. If we look at the figures in Table 1 below we can see that health spending in England will increase ‘in real terms’ over the next five years.

Given the figures above, can we expect our experience of the NHS to get steadily better over the next 5 years? At the planned levels of spending, almost certainly not. There are three main reasons for this. Firstly, changes in the population, which is expected to increase, as well as becoming older on average. Secondly, the impact of advances in medical technology. Thirdly, the human labour-intensive nature of health and care in general.

The Office of National Statistics (ONS) estimates that UK population growth will be around 0.7% per year over the next decade. Since the annual increase in real health spending shown in Table 1 comes out at 0.68% per year on average, this immediately wipes out the spending increase. Real health spending per person will be more or less exactly the same over this time.

Technological advance in medicine frequently improves the quality of care rather than its efficiency in strictly monetary terms. An additional diagnostic test or treatment may significantly improve the outcome of a disease but require additional spending and professional time to implement. In a strictly market system of healthcare each of us would be forced to make a decision as to whether we gave up other goods and services for this additional treatment. The likelihood of us doing so would increase the wealthier we were, since healthcare appears to be what is known by economists as a ‘normal good’, something that we tend to want more of as we get richer. For a public system such as the NHS in the UK, we don’t make these decisions individually but through the democratic process. We have to collectively decide how much we want our government to spend on health along with how much taxation we are willing to pay to provide this. The aggregation of our individual preferences for better healthcare as we grow richer suggests that public healthcare provision should increase as our economy grows and that we should be willing to pay the additional tax that requires. If spending on healthcare increases at the same rate as economic growth – which takes account of both population growth and national income growth – then we should see healthcare spending remain at a more or less constant proportion of GDP over time.

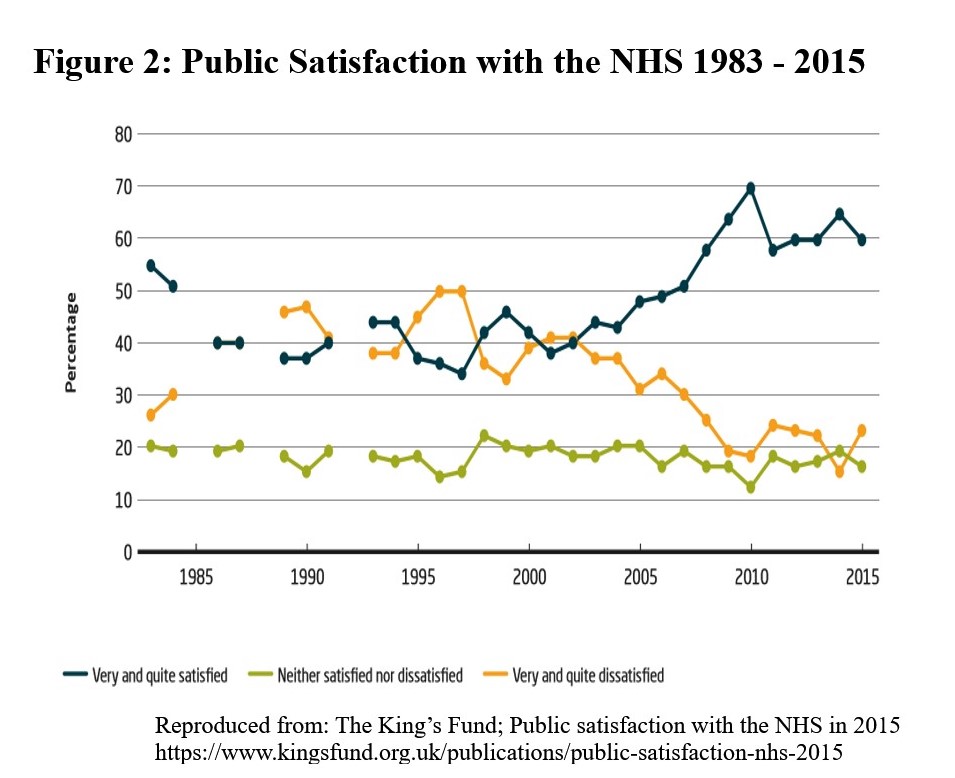

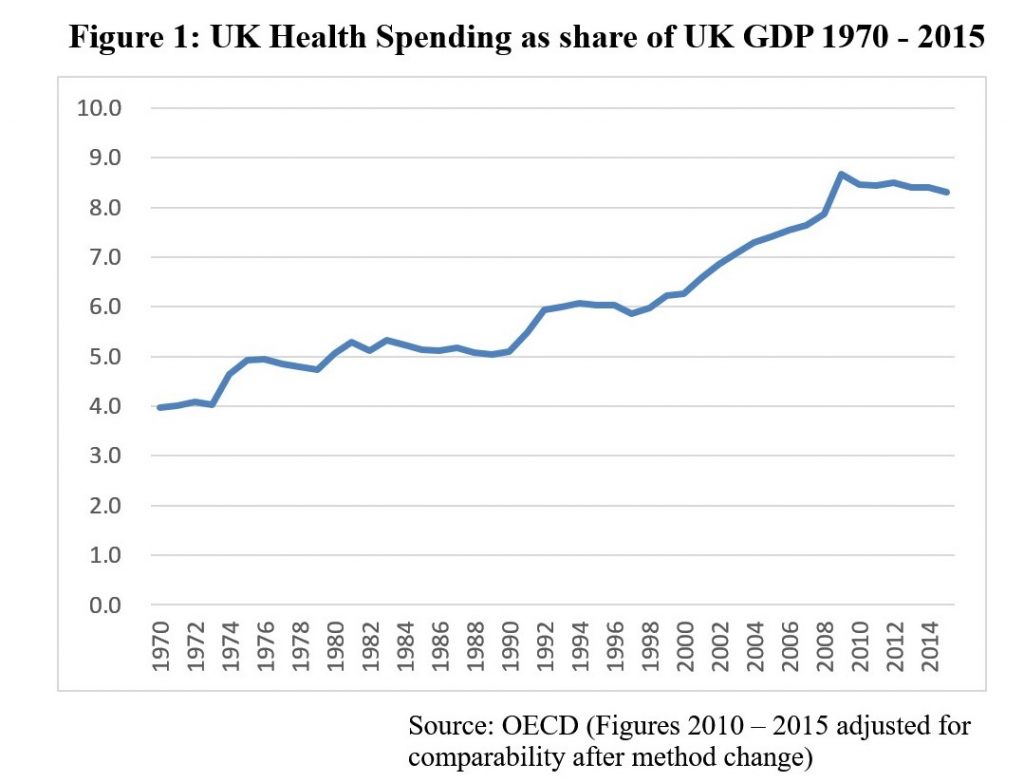

Figure 1 above, however, shows a rather different picture. Total UK health spending, including public and private, rose from 4% of GDP in 1970 to around 6% through the mid-1990s. By this time there was major concern about NHS standards from professionals and growing public dissatisfaction as shown in Figure 2 below. From 1997 until the Financial Crisis of 2008 there was a steady increase in the share of GDP devoted to health, rising to around 8.5% in comparative terms. (The apparent spike in spending of 2009 was not due to profligacy, but due to the rapid contraction in real GDP following the crisis.) This extra spending over the 2000s coincided with a steady increase in satisfaction, as well as improvement in other health measures in the UK such as a reduction in deaths from conditions amenable to healthcare.

Productivity and Public Services

Productivity and Public Services

Why should it have required these increasing GDP shares to have produced a satisfactory NHS? To explain this we can turn to an insight of the eminent American economist William Baumol, which now has some empirical support. He identified that certain sectors of the economy are intrinsically likely to suffer from relatively low productivity growth. These sectors are characterised by a significant correlation of their quality with the amount of human labour involved in their production along with being difficult to standardise. As Baumol points out, teachers who shorten class times or increase class sizes and doctors and nurses who spend less time with their patients are likely held to be ‘short-changing those whom they serve’. Standardisation is difficult in teaching and medical care because they are ongoing processes requiring individual assessment and re-assessment as well as tailoring of approach to personal learning or treatment and care needs. Since other areas of the economy can increase productivity more rapidly, if wages then rise more slowly, then the relative cost per unit of these high productivity goods will fall. Since market forces will tend to push all wages up – since over time we can expect people to shift into the higher wage sector until wages are similar in all sectors – the relative costs per unit in the low productivity sectors will rise. To keep a constant proportion of those goods in our ‘basket’ of all goods we have to spend a greater share of our total income on the low-productivity goods. In the era of globalisation, when the UK imports a large proportion of its manufactured goods, increasing productivity and lower wages in the exporting countries are also likely to have an impact. Discrepancies in unit costs arise here from the need for relatively low-productivity personal services such as medicine and care to be produced within the UK.

Baumol notes, however, that even if the relative costs of some goods, such as healthcare, are rising we can still continue to obtain a greater amount of all goods, because the lower costs of the high productivity goods mean that we have to give up less of these than we otherwise would. Translating that to our observation that healthcare spending as a share of GDP has risen since 1970, this need not mean that we are therefore having to sacrifice the enjoyment of other goods and services (public or private) to allow this increase.

Taking things a little further it’s worth noting that both education and healthcare, while being candidates for Baumol’s so-called ‘cost disease’ are also frequently provided and/or funded collectively. There appear to be good reasons for this overlap. In healthcare what makes it difficult to raise productivity is the reliance on knowledge and skills embedded in a human agent – the doctor, nurse or other health professional. That a medical consultation or episode of nursing care is often unique to the individual and circumstances, thus making it difficult to replicate on an efficient basis, also makes it difficult to assess its quality before or even after it has taken place. This makes it difficult to ‘shop’ for our healthcare in the way that we are happy to do for most goods and services we consume. Yet the benefits of personal health are also benefits to society in more effective workers and lower disability rates, so we all have an interest in everyone receiving adequate health care.

The reliance of healthcare on trained humans rather than programmable machines demands planning long before any market signals are available. It takes at least a decade to train a hospital specialist doctor, nearly as long to train a general practitioner and perhaps half of that to fully train most other healthcare professionals to be able to practise independently. For new health or care providers to be set up, or for existing providers to adapt to changing choices may be severely limited by these factors, which makes market responses sluggish to any demand changes. Similar considerations apply to education, social care, police protection and perhaps libraries. While the possibility of machine takeover of many of these functions, including medical consultation is being touted, it will surely be some time before this becomes possible, and longer still before it becomes generally accepted.

This all suggests that not only should we expect healthcare expenditure to increase (both public and private) but that public expenditure in general as a share of GDP may need to increase as the economy expands in order to maintain the adequacy of those services which may be better provided publicly. Once again it is important to emphasise that while this does mean that taxes as a proportion of incomes and wealth must increase, this need not mean that citizens have decreasing real disposable income. The cause of the increased share of GDP for public services is in part due to increased productivity in the production of market goods, so we can purchase more of these at lower cost despite higher tax rates. Those higher tax rates however are the almost inevitable cost of maintaining acceptable standards in our universal public services. The current difficulties in the English NHS are clear evidence that this is the case. We can see from Figure 1 that the GDP share in UK health spending has been more or less flat since 2010 although real spending has increased. Despite relentless emphasis on cost-cutting, the service is suffering several structural problems: there is a shortage of care places as a consequence of major cuts to adult social care budgets that have resulted in nearly 90% of English councils unable to offer any support for people with ‘low to moderate’ care needs; there is difficulty in doctor and nurse recruitment, the causes of which are probably a combination of poor workforce planning, lack of infrastructure support and suppression of the natural increase in expected pay rates as general productivity in the economy improves; and many units of the NHS are in financial deficit.

Prospects for the NHS

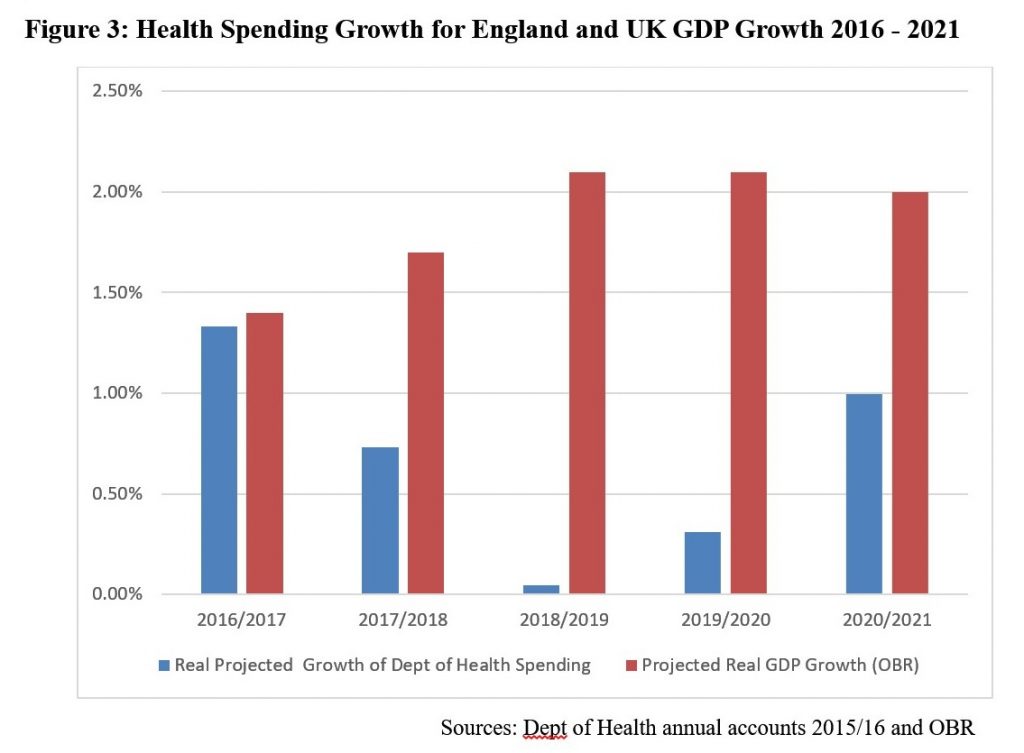

Can we expect things to improve given the government’s planned health spending in England up to 2021 shown in Table 1? Figure 3 below doesn’t show much room for optimism. In the current period (2016/2017) projected spending growth only just matches GDP growth, while in the following years we can see that spending growth will fall well short of GDP growth. The inevitable result is that the total GDP share of health spending will be considerably lower by 2021 than it is now, rather than higher.

A Commission Report from the King’s Fund health policy thinktank argues that the government’s health spending plans are not credible ‘given the impact of the aging population, the return of economic growth, continued technological advances and rising public expectations of what a decent health and social care system should provide’. The future age change in the population will be considerable, with 40% more 65-85 year olds by 2032 than there were in 2012 and double the number of over-85s over the same period. As might be expected, the costs of health and social care and the number of hospital admissions are considerably higher for older people. The King’s Fund suggest that a 3.5% annual real-terms rise in NHS expenditure, combined with the provision of ‘moderate’ and ‘higher’ social care needs free at the point of use, would bring total health and social care expenditure up to between 11 and 12 per cent of UK GDP by 2025. This compares with the 16.9% of GDP spent by the US and the 11% spent by France on healthcare alone in 2015.

If UK economic growth continues at an annual average of 2%, by 2025 GDP at 2013 prices will be around £2.2 trillion compared to £1.8 trillion in 2015, an increase of £400 billion. In 2013 terms an increase in spending on health and social care to 12% of GDP would represent around an additional £60-70 billion annual spend in 2025. Yet even with this increase in health and care expenditure, the nation as a whole would still have over an extra £300 billion to spend on all other goods and services, public and private. The King’s Fund’s recommendation is thus eminently affordable.

Funding an acceptable NHS

Although we can spend a greater share of future national income on health without reducing our ability to enjoy other goods, the necessary transfer of some of that additional purchasing power to the NHS does require an increasing proportion of that income to pass from private hands to the public sector. The King’s Fund Commission come to the conclusion that for the most part introducing new charges for NHS services is unlikely to raise significant amounts and may have detrimental effects on access to healthcare. Their exception to this is the combining of a reduction in prescription charge exemptions with a reduction in the charge itself, perhaps from the £8 of the current charge in England to around £2.50 with a capped annual total payment. They also recommend the targeting of some benefits that are currently available to all pensioners, irrespective of income. More general tax changes suggested are some increases in National Insurance and additional wealth and property taxes. The latter make additional sense in that currently the sicker proportion of the better-off elderly are disproportionately liable for their own care costs. While a wealth tax for this purpose would also target the wealthier, it would at least be shared across all of those in a particular bracket, whether healthy or unhealthy. Whatever choices are ultimately made here, avoiding making them by pretending that current health expenditure plans can produce satisfactory outcomes is socially and politically unsustainable. The general link between public services and slower productivity suggested above means that this also applies to other important services.

2 replies on “Explaining the NHS Crisis: Lies, Damn Lies and Health Spending”

Ok, so what you’re really talking about is a 3 per cent GDP increase in taxation spread over 8 years.

The idea that this is ‘affordable’ and without “without any great sacrifice in our enjoyment of the other goods and services that the modern economy has to offer” depends on two assumptions and a maths problem.

The first assumption is that there’s enough growth to pay for the extra tax without denting existing post-tax incomes. The scenario you paint is one where it would be, although that’s an average, and for some people it would be less certain.

The maths problem is that you need to factor in maintaining current GDP levels of public spending commitment elsewhere, which leaves a much smaller pot for increased private consumption.

The second assumption is that people would be happy to lose such a large chunk of their marginal income gain for one purpose. Let’s say that incomes went up on average 1.5 per cent (16 per cent over ten years, leaving the rest of growth to population change). You’re expecting people who currently choose to take <10 per cent of consumption in healthcare to want to spend something like 25 per cent of their marginal increase in consumption on healthcare.

Now healthcare probably is a luxury good — but the necessary income elasticity just isn't there to make this seem like a no-sacrifice option (check out opinion polling on raising taxes to pay for the NHS — which even then is often taken to mean "raise taxes on others"). Your assumption that because people will have 'some extra goods and services' goes against what we know about how people view consumption choices.

Hi Anonymous – I’m sorry you don’t feel able to identify yourself. Growth would have to be less than 0.4% on average to result in the proposed additional health and social care spending actually crowding out other public and private expenditure. I left open the question as to whether the additional non-health expenditure would be public or private, but you are right that if public expenditure in other areas were to increase in line with GDP (currently most are actually declining in real terms, never mind in proportion to GDP) then this would mean relatively less private consumption. Of course it is a political choice as to whether the additional revenue will be forthcoming to improve health and social care – but that is my point.