Cryptocurrency – more fiat than ‘Fiat’

I have previously written about Bitcoin, explaining why I don’t believe it has any future as a replacement for so-called ‘fiat’ currencies. There are various reasons I cited for this, the most important being that actual state-backed currencies are not ‘fiat’ at all. They are not given value simply by decree, but derive real value from their demand. This demand is created by governments and central banks for the legally-enforced payment of taxes in their economy of issue, and the legally and reputationally-enforced repayment of loans to commercial banks. The latter are associated with banks’ creation of money on the back of their access to reserves of state-issued currency.

Bitcoin and other ‘cryptocurrencies’ have no such backing, but are perceived to acquire value through the bait and switch of so-called ‘mining’. This mining involves the owners of the decentralised computing resources using them (at great energy expense) to irreversibly record transactions on the ‘blockchain’. They are then rewarded in the very medium they are purportedly transferring.

But while the blockchain technology may have some value as a method of securely recording ownership and transfers of ownership without the need for a central authority, its use does not magically transform the objects referred to into things of value. This is as true of cryptocurrencies as much as the more recent phenomena of ‘Non-Fungible Tokens’ or NFTs. This fake transformation is more akin to the supposed role of value declaration in national currencies than to the reality of their central and commercial bank backing.

Bitcoin – got to be worth a punt though…?

At least with cryptocurrencies themselves there is generally no question as to what ownership of a unit of one of these entails. The blockchain-registered owner of Bitcoin, Ether and so on can use, transfer or dispose of her currency in any way she wishes, so long as (in the case of a transfer) she can get another party to accept them. This may not be the case with NFT ‘ownership’, as we shall see.

Staying for now with Bitcoin and the like – while ownership rights may be clear, what of the utility of ownership? Is Bitcoin worth acquiring for any purpose? The social purpose of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies is supposedly that they are a way of transacting for goods and services (a ‘medium of exchange’) beyond the reach of national and supranational regulatory authorities. Whilst this use is clearly of value to those wishing to conduct trades that are justifiably illegal, it is argued that in many cases transactions are regulated or monitored by the authorities for unwarranted reasons.

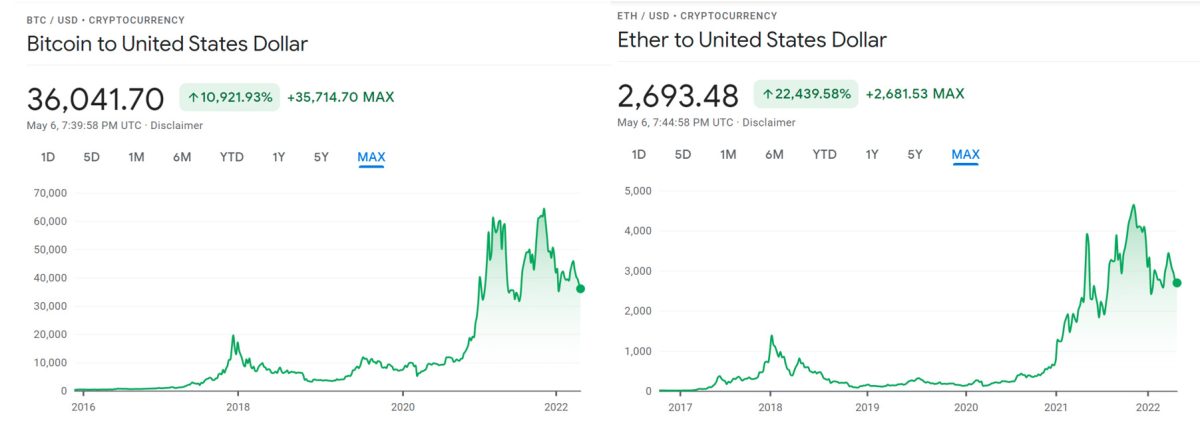

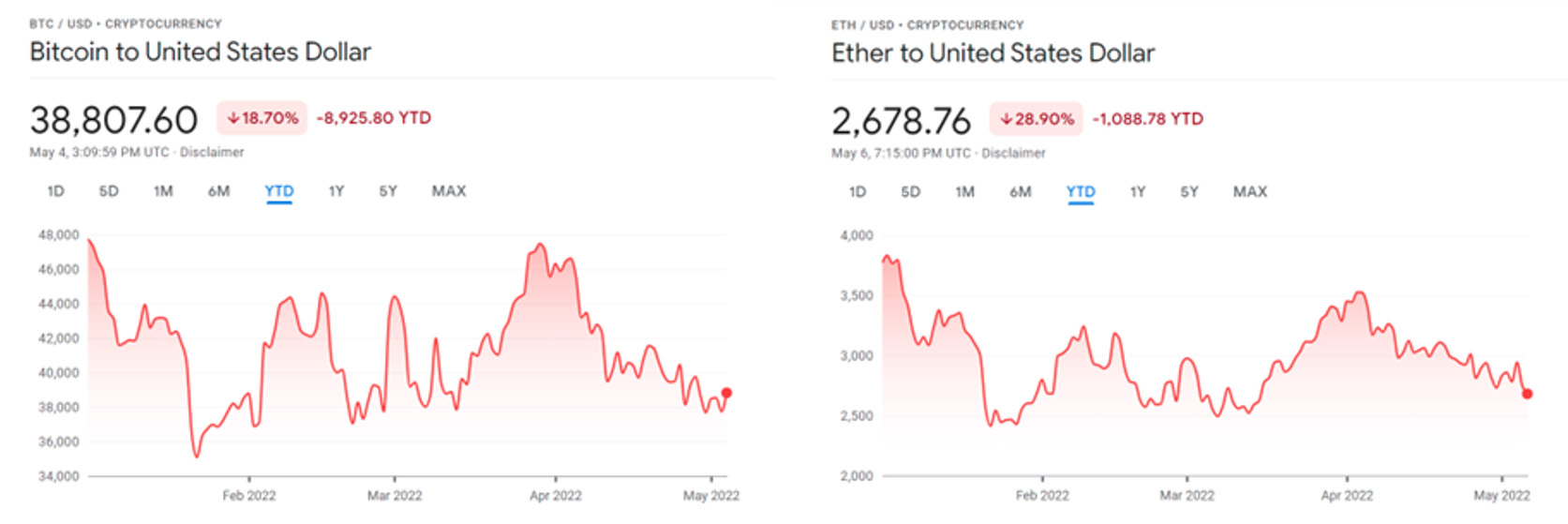

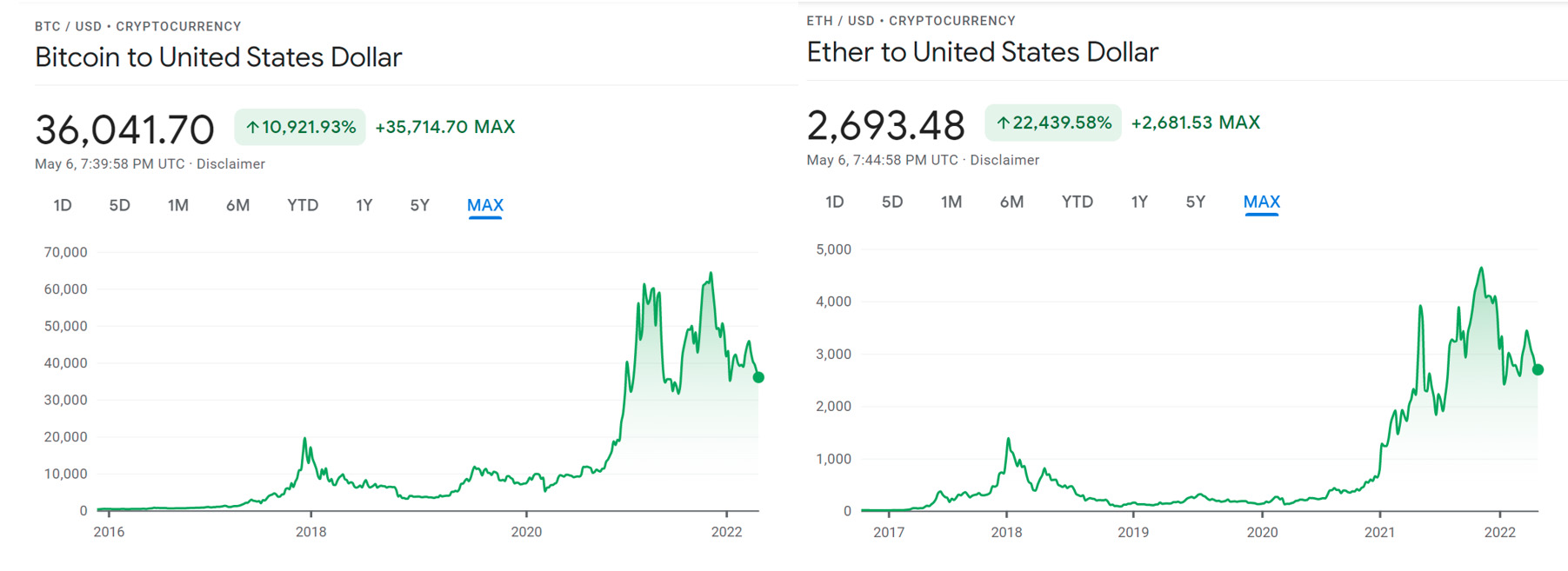

In the latter case cryptocurrencies are a socially beneficial means of bypassing such intrusion. Be this as it may, a medium of exchange benefits from having a stable value. Without this the timing of sales and purchases of real goods has to take account of the fluctuations in the value of the medium itself. As a result of the lack of solid value backing described above, Bitcoin and similar currencies singularly fail on this account, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below. As a result, cryptocurrencies have generally failed as a medium of exchange except in some niche areas.

Since these currencies have no ultimate use and are unlikely to be widely adopted as replacements for stable centrally issued currencies, what can possibly be said in their favour? The one attractive feature they do appear to possess is that their value in terms of state currencies has generally been increasing since their initial introduction. Whilst demand may be small in currency terms, it has so far tended to exceed supply.

Those that entered the game early and ‘HODLed’ or held their crypto while it rose in value can feel very pleased with themselves. They can (and frequently do) tell us sceptics that we are all idiots for not believing in it. But apart from the fact that HODLers have a vested interest in us ‘getting into crypto’ as our purchases are the means by which their holdings increase and realise value, the past is no guide to the future.

No Fair Market

A fair market reaches a price determined equally by the beliefs of all participants, whether they are looking to buy or sell. All available information is utilised by the participants. As a result the only factor that should change the price in such a market is new information. Since this information, by definition, cannot be known in advance, whether its impact on the price will be positive or negative is unknowable. As far as a prospective purchaser is concerned the next price movement may be up or down – one is equally as likely as the other – and the same is true of cumulative movements in the future. The most likely (although not actually very likely!) price at any point in the future is the price that exists now. The expected gain in value of an asset purchased in such a market is therefore zero.

The caveat to this is that this applies to a market that is fair, and in which participants are behaving rationally. Few markets comply with these criteria, least of all an unregulated one like the crypto market. Since it is in the interests of crypto holders with market and media power to influence the market, they will do so. Since crypto has virtually no value beyond its price movements, price movements in favour of the market movers are movements to the detriment of all other holders. The ordinary holder’s most likely outcome of their crypto holding is therefore not zero, but a loss.

When to Buy…? Also, When to Sell…?

One way to try to buck the trend might be to invest more time and attention to the crypto market than the average punter – so as to be aware of the exact moment your holding has increased in value and so sell at a profit. Firstly, this comes at a cost of time and so of (real) money. Secondly, it’s not a sustainable strategy. So, I purchase one Bitcoin for $20,000. Since I expect the path of its value to be random around its current price, I can expect that at some (unknown) point in the future it will be above my purchase price. At that point I sell at $21,000. Success – I’ve made $1000 profit, which is 5%.

But now what do I do? Do I stay out of the Bitcoin market, or do I stay in? If it made sense to enter the market before, why would it make sense to stay out now? But if I stay in, when ultimately do I get out? The answer to the latter question is impossible to answer because there is no knowing when the maximal gain has been made and the reality for an individual is that the time to sell a long-term Bitcoin holding will depend on considerations outside the market. At some point I will have to sell Bitcoin to make a purchase of real goods, to pay taxes or to repay a debt. I will have, at best, limited control of the timing. Since the most likely crypto gain in any specified time-frame is zero in theory, and negative in practice, I will probably make no gain, and very likely a loss.

Stick to Real-World Investments

It could be argued that investment in stocks and shares is no better, and when it comes to individual securities, this is pretty much true. Without privileged information future movement of the market price for these is also pretty much random. Although many come with the prospect of regular dividend issue this prospect is always factored into the purchase price. There are two advantages even here, however. I can buy securities on regulated markets, where there are rules on the use of inside information and market power, levelling the playing-field somewhat. Secondly, the underlying assets of the issuing entity may have some residual value even after it ceases operation. (It may also have debts, but limited liability laws absolve stockholders of responsibility for these.) Such a residual value puts a non-zero floor on the value of my investment.

More importantly, when I purchase stocks and shares I can spread my investment (diversify) across a wide range of sorts of real activity. As the world population increases and human innovation continues, it is a reasonable assumption that the scale of these activities will increase in aggregate. The revenue, profits and dividends of the companies in which I am invested will also increase in aggregate. And even if global economic activity declines in aggregate, I will not be relatively worse off than the average investor.

Crypto investments, on the other hand, cannot be truly diversified. Individual cryptocurrencies may appeal to different subsets of the deluded, but ultimately their value depends on the same delusion or category error – that the value of something can depend not on what can be done with it, but with the method by which it is transferred. As soon as this single delusion is punctured (or once the limits of its spread are reached) the value of all of these ‘currencies’ will descend pretty much to zero together. The only realisation that is required to produce this effect is that other investments have a better expectation of holding real value. Conversely there is no reason to suppose a general increase in crypto value in line with aggregate global growth, since there is no real-world activity underlying these currencies. Even those desperate for a big gain at almost any risk will see that they might as well invest in some moonshot tech startup. At least that has some possible if highly improbable social value.

Delusion and NFTs

To return to NFTs. The same delusion is at work as with cryptocurrencies, but in many cases the delusion is worse. The fact that ownership of ‘something’ is recorded on the blockchain rather than by central registries or certificates of transfer or receipts does not increase its value. Indeed the legal non-enforceability of such ownership is value-diminishing. Blockchain-recorded ownership of ‘nothing’, which is what many NFTs amount to, most certainly does not give it any value at all.

Whilst it is true that the value of some physical artworks and collectibles can be pretty hard to fathom, ownership does give an exclusive right to view, display and touch the object. The ‘right’ to call a digital file your own, even when others can view that file, copy that file and edit that file, is not a right worth having. Even if it were, there is currently no route to the legal enforcement of NFT rights. This is not ownership in any way that has been understood in the history of commerce.

Even more absurd, it is now possible to ‘purchase’ moments in time and space, such as iconic sporting feats, even though this does not give any exclusive right to audio and video recordings of these feats or access to their performers. The delusion is that ownership of these moments exists with certain bodies, such as the International Cricket Council (ICC) for cricket ‘moments’ being marketed as ‘Crictos’, and so only they can license them for ‘sale’. No amount of logical contortion should be allowed to make such nonsense stand up.

Worryingly, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer has jumped on the NFT bandwagon with the suggestion that the Royal Mint (a government-owned limited company) create an NFT of some unspecified form. How such an entity could have real value is difficult to imagine. Worse perhaps, the Chancellor has spoken of ‘his ambition to make the UK a global hub for cryptoasset technology’. The City of London already has a deserved reputation for money-laundering. Now it can add servicing global scams to its revenue stream.

Conclusion

In summary, the phenomena of cryptocurrencies and NFTs are the result of a category error by those without understanding and of a bait and switch by those with it. The blockchain technology may have some value as a decentralised method of recording ownership and transfers of ownership, but it does not change the nature of ownership. To be of benefit, ownership must be enforceable, be of an entity that has some ultimate (even if fairly esoteric) use value and come with genuine rights to realise that use value. Cryptocurrencies and NFTs always fall down on one or more of these criteria.