Politics and Morality – Where Conservatism gets it Wrong

Tim Montgomerie wrote an interesting piece a while ago on ‘How the Left went Bad’, which asserted the necessity for Conservatives to ‘take the moral high ground’ from Labour.

Now, I don’t think talking about ‘morality’ gets us very far in politics – different morals are too irreconcilable. But Montgomerie thinks Labour’s advantage is in appearing to ‘have our hearts in the right place’. Of course, since this goes along with ‘messing up economies’ and ‘incompetence’, the true moral superiority and a ‘much superior approach to social justice’ lies with his team, through ‘sound finances, strong families, school choices and unshackled job creators’.

Some of Montgomerie’s arguments are just wrong or odd. The UK’s current debt burden was not acquired by ‘borrowing during the good years’, but by the effects of a global financial crisis. ‘Incompetent’ Labour apparently managed to preside over a decade of prosperity. Delivering ‘fairness’ appears to include public sector pay and conditions falling to match those of the private sector. But despite all this he picks out something important about the difference between the characteristically left of centre and right of centre view.

The left generally sees human misery and disadvantage as something to be tackled directly and where it is occurring. This is why Mr Montgomerie perceives Labour as ‘relentless’ at presenting ourselves as ‘the party of the working class, minorities and the little guy’. We are. Many of us have personal or professional experience of what it means to be in these groups. This also explains why we have seen the state as an important player – since in a capitalist economy it alone has the power to mobilise the resources required for major direct interventions. What might be perceived as Labour’s ‘morality’ is our more directly human response to the problems experienced by other humans.

This doesn’t necessarily make the left’s approach better. If the market alone produces the best possible outcomes for all, then it is actually inhuman, and perhaps immoral to interfere with its workings. But of course the right always cite Adam Smith’s economic ‘invisible hand’ while forgetting his admonition about those ‘of the same trade’ conspiring together socially. Taking both together, the self-organised bounty for all of the free-market is largely a myth – both at the theoretical and empirical level. As a result economics, taking only the invisible hand seriously, has proved remarkably poor at predicting large-scale outcomes, both in aggregate and in terms of individual welfare. Away from extremes the beneficial outcomes of both demand-side adjustment of government activity and supply-side deregulation, tax-cutting and welfare withdrawal are doubtful, and if present pretty small. But what is in no doubt is that cuts to social support, job insecurity and environmental despoilment cause direct human hardship and loss of life-quality.

So the right’s instrumentalism – putting faith in the market mechanism rather than human reality – even where it is honest, is cruelly mistaken. And it might be suspected that often it is not honest, since it clearly suits the wealthy to support a system that mobilises their existing wealth effectively in the pursuit of its enlargement, and in the pursuit of power in other spheres of life. The virtue of success, where success consists of ‘making money’ – this very phrase is ideological – is an ideology that suits the rich, those that believe themselves to be rich and those that aspire to be rich. It also appeals to those that ‘frame’ their thinking about life according to what cognitive scientist George Lakoff has called the ‘strict father’ model – even when the actual policies pursued are against their current self-interest.

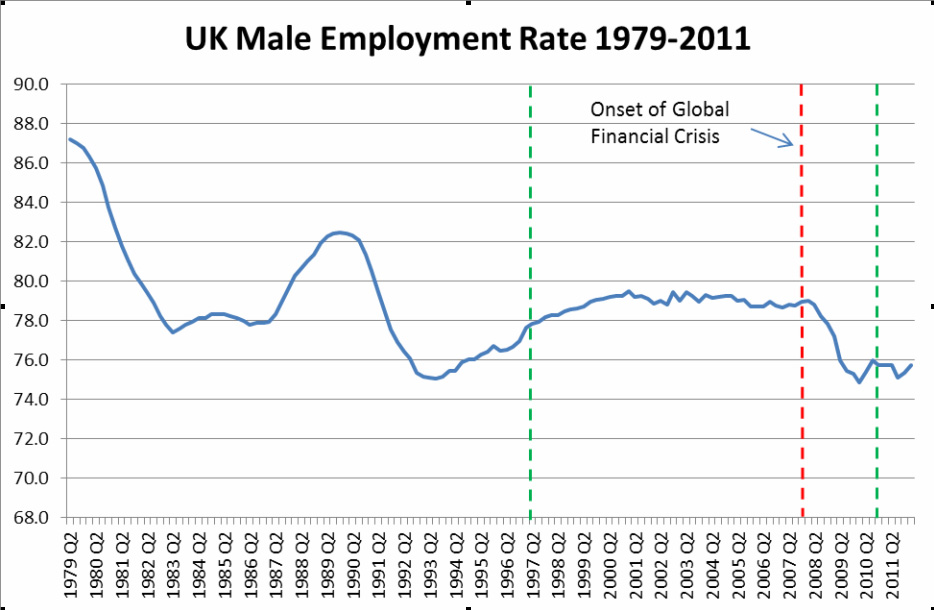

No doubt the right and the left define ‘social justice’ differently. But at any rate, right social justice must at least allow us to work for our material share and be rewarded when we do. But the relative Conservative record here is either unremarkable or poor. UK male employment was 87% of working age men in 1979 when Mrs Thatcher took office, but by 1997 this had fallen to 78%. New Labour under Blair and Brown actually managed to halt this trend, keeping this figure close to 79% from 1999 until 2008. (See Figure 1 below)

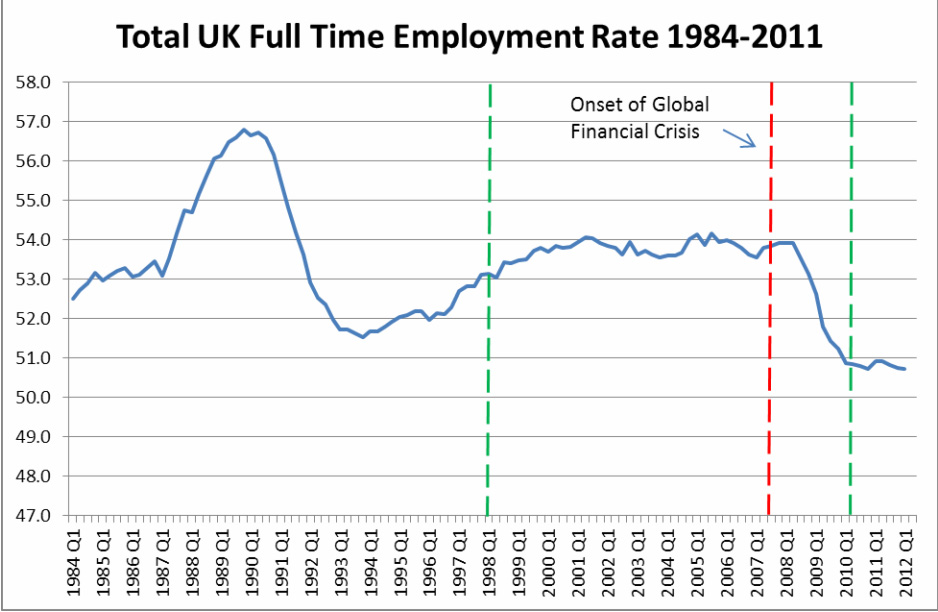

As is well known, female employment has risen considerably to offset this trend for men, but the period of Conservative government between 1984 and 1997 (no breakdown between full and part-time working is available from earlier) produced no net increase in the total full-time employment rate among those of working age. The rate was 53% before the Lawson boom and bust, rose and fell precipitously, and then gradually made it back to 53% by the end of the Major administration. New Labour managed a small increase from 53% to 54% before the global financial crisis. The rate then fell to just under 51% and has stayed around there over the two years of the Coalition. (See Figure 2 below)

Source: ONS Labour Market Statistics

Along with this questionable record on allowing access to the market bounty, the Conservative record on the results is also poor. Calculations by the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggest that the average annual income gain for the bottom half of the population was around 50% greater under New Labour than in the years of Conservative rule from 1979 to 1997.

Montgomerie also claims that Labour has something ideological against the ‘two parent family’ and against faith-based charities. Thus we fail to make use of important weapons against poverty. This argument is based on the right’s typical confusion of freedom with freedom to discriminate – the latter actually being a net loss of total freedom. Marriage should neither be the property of the churches nor of the state. It represents a commitment of two people to each other for their mutual benefit, with the state in the role of recorder and if required, arbitrator. The value of marriage for society lies in that mutual benefit, perceived by the couple. Without it the state itself does not have a stake in the contract, and so should not encourage, discourage or generally restrict competent adults in entering into marriage.

If faith-based charities have a part to play in providing social goods it is because many religious people themselves focus on the human rather than the instrumental. Yet this is in conflict with much religious teaching which does have a strong instrumental flavour. Suffering in this world is downplayed in favour of joy in the next. This view can play no part in public policy.

If Labour often gets it right when it focuses on the human, why do things not turn out better, both in material outcomes and sometimes in the integrity of Labour politicians? This is primarily from the bad faith of those that impose a free-market on the poor, the better to manipulate and subvert that ‘market’ for themselves. The result is a constant battle to shore up the gap left by inadequate employment, wages and support as the available resources are concentrated in fewer hands. No wonder the benefit system becomes overcomplicated, public services become over-burdened, families become fragile and union members struggle to maintain eroding pay and conditions. These are not policy choices of the left, but the symptoms of an underlying injustice which the right appears to do all it can, whether knowingly or not, to perpetuate.