Understanding Money – a non-technical account of the essential role money and its creation plays in a modern economy. This article was previously available as a pdf, but I have now posted it as a blog in its own right. Since it was originally written in 2010, I have made a few revisions and additions.

Introduction

Most of us have little idea of what money is and where it comes from. When we think of money, we think of bank-notes and coins. We know that most money is held in bank accounts, but even then we have an image (although most of us are probably aware that it isn’t quite an accurate image) of these notes and coins being held for us by the bank or lent out by the bank to make money for them (and hopefully us, if the money is held in an interest-bearing account). In fact the reality is about as far away from this as it is possible to imagine.

Of the total amount of money (adding together bank-notes and coin held by the general public and the value of all bank accounts in the UK), the bank-notes and coin make up only around 3% ! The reality is that the vast majority of all money exists only as a record held in someone’s name by some bank or other. How can this be? Where does this money come from? Where does it go? In this article I will attempt to answer these questions, and in doing so explain the benefits and the potential downside to our monetary system.

How Money is Created

The reality is that money is not something that has value, like a gold bar or a tool or even a qualified plumber! Money is really a symbol of a relationship between two individuals or social groups (such as firms) that have agreed on the supply of something valuable. One party is promising to provide the valuable thing and the other is accepting that promise. Quite commonly this valuable thing does not yet exist, but is going to be produced by a firm using work from people accepting a money wage. Since there are two parties to the relationship represented by the thing that we see as money (banknote, coin or computer entry) there are also two sides to money.

For those that have ever kept accounts, this should not be such a strange concept. The standard technique of financial accounting is known as double-entry book-keeping. As the term suggests, all transactions are entered twice, as a credit and again as a debit, indicating the source and the destination of any funds. The total debit and total credit entries must always match, and this provides an additional check on the accuracy of the accounts. Immediate debits are expenses; immediate credits, income. Debits due in the future are liabilities; credits paying out in the future, assets.

Using the double-entry system money is always simultaneously a liability for one party and an asset for another. It is a liability for someone who has promised something to whoever holds the money. For whoever does hold it, the money is an asset, because they are now the one to whom the promise applies. Since money represents a promise it is not really created, as is sometimes claimed, ‘out of nothing’. Money is created out of a credible promise to provide something to someone else at some time in the future (sometimes a short time in the future, sometimes a longer time). This promise is then registered as a transferable record.

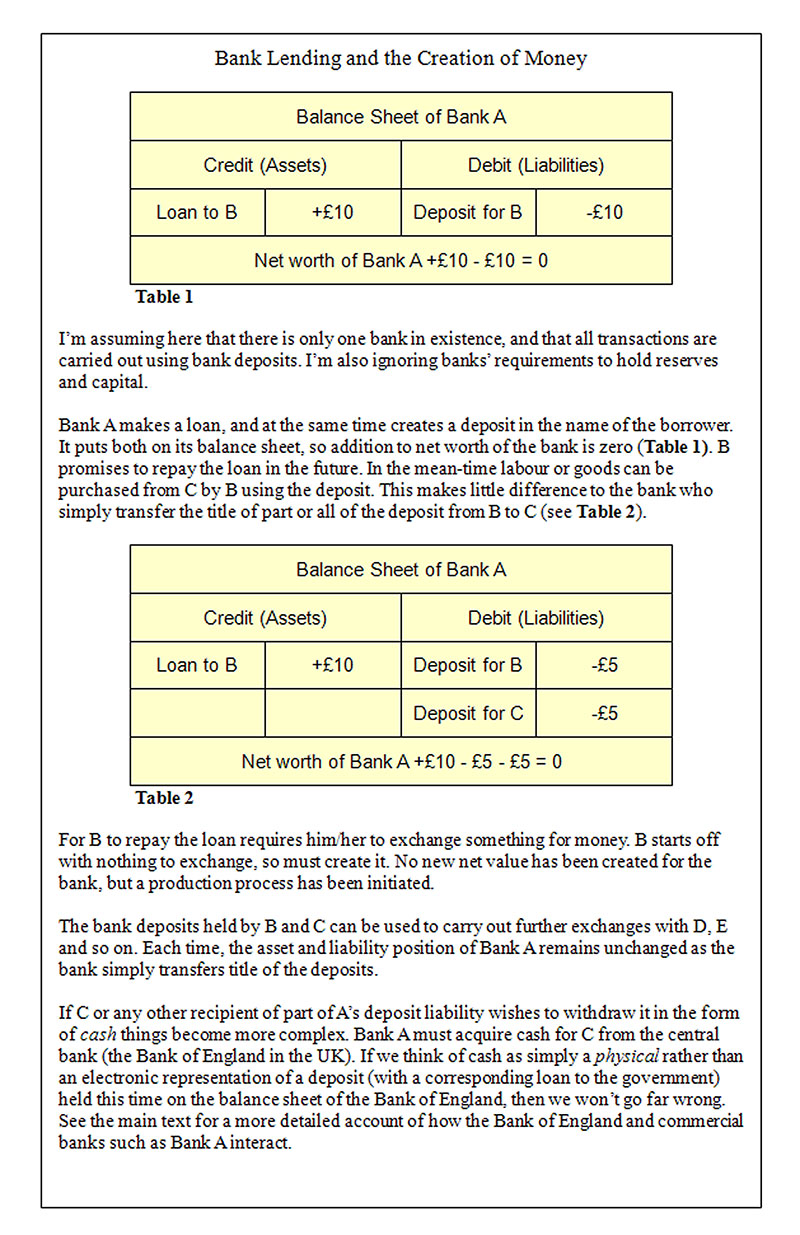

If you are alert you may have noticed that what we have described so far could just be transferable IOUs. But there is a vital difference between money and an IOU issued by an individual or firm. The acceptability and value of an IOU depends on the confidence the holder or recipient of an IOU has in its individual issuer and in the value of what has specifically been promised. Both of these may be difficult and time-consuming to assess properly. Yet all money has the same acceptability and value. How does this come about? It happens because money can only be issued through organisations with a special status guaranteeing as far as possible that the promises associated with money are actually kept. These organisations are called banks. An individual or firm makes a promise to produce something. (For the individual this may just be his own work.) If a bank believes that the promise is a credible one and that what is to be produced can be sold (in exchange for a wage in the case of work) and so allow the borrower to repay, then the bank creates a loan on the credit side of its own balance sheet. It’s a credit because for the bank it’s something due to the bank in the future. At the same time, it creates a money deposit on the debit side of the same balance sheet (it’s a debit because for the bank it’s something that the bank must transfer away or pay out on request). In exchange for the promise of the borrower to repay the bank the borrower has been relieved of the liability side of the issued money, which has now been taken on to the bank’s own balance sheet (as shown in the box below).

Since the loan and deposit quantities must be equal, for the bank the credit and debit cancel out leaving its net asset and liability position apparently unchanged. When the loan is repaid, the bank’s credit entry is erased and the equal debit entry from the borrower’s deposit account is also erased. In this sense, it can be said that when a loan is repaid ‘money is destroyed’.

Banks get their special loan-issuing and deposit-creating status in several ways. Firstly, they deal with lots of borrowers and depositors, so that they develop expertise in assessing the likelihood of borrowers to repay their loans and can accept the risk of a certain number of un-repaid loans. Secondly, again because they deal with a large number of borrowers and depositors, and also because the money they issue individually can be transferred to other bank deposits (I explain below how this is possible) bank deposits can be exchanged for many different types of goods and services, not just those that were promised specifically to create those deposits. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, banks in a modern economy have extensive support from the state. Repayment of bank loans is enforceable through the legal system. Moreover, the state central bank issues and guarantees its own money using essentially the same mechanism already described but with the government as the borrower. Holders of bank deposits can convert these into state money in the physical form of bank-notes and coin, and also do so automatically when they pay taxes or purchase bonds from the government. State money (often referred to as high-powered money) also forms a common currency that allows the seamless exchange between banks of the deposits they have individually issued. (To ensure that demands for cash and transfers to other banks can always be met, banks will at all times hold some state money reserves.) Ultimately, even if banks run short of cash or fail because they make too many loans that go bad, the government (up to a certain amount) guarantees bank deposits, making them a safe form of individual wealth.

Rewards and Risks of Banking

What does the bank get out of doing what we have described? They expect to make a profit on the difference between the loan interest rate charged to borrowers and their costs of issuing, monitoring and enforcing repayment of loans. A large part of this cost is the obtaining of reserves of state money to provide for demands for cash, tax payments and the net transfers of bank deposits. (This gives a role for the central bank to influence the actions of banks by adjusting the cost of reserves through the ‘base’ interest rate charged for lending them.) Another cost is that imposed for ‘bad loans’ that despite the efforts of the bank fail to be repaid. In this latter case, the bank must charge the loan quantity against its capital, so that ultimately the return made by its shareholders is reduced by this amount.

What Are the Social Benefits of Money?

Money has been an incredibly powerful agent of economic and technological development over the last few hundred years. It has achieved this in two ways. Firstly, it makes the exchange of goods and services much, much easier. Without money, we would be limited to just swapping things we already have with each other (what is known as barter), or relying on individually-issued IOUs (the drawbacks of which I described above). Barter needs two people or firms to match up in a special way. One of the two must want something the other has; while at the same time the second must want something the first has. This matching was called a double co-incidence of wants by the British Victorian economist William Jevons. In a modern economy, with the huge variety of goods available and the different tastes that we all have, the chances of two people meeting each with the right goods at the right time is going to be an incredibly rare occurrence. A double co-incidence of wants is almost never going to happen. The existence of money, as a form of place-holder for one side of a two-way exchange, means that one person or firm can exchange the good they have for money, and then travel or wait until the good they want is available. Moreover, the sort of money we have today uses little or essentially no resources to produce, is easily portable (or often doesn’t need to be transported at all) and doesn’t decay or expire.

Note that the advantages of money I have just described relate to money that is already in existence. This is in contrast to the other, and probably more important, major benefit of a money system, that relates to the advantages of being able to create money. I described how banks create money deposits as part of the representation of a credible promise of an individual or a firm to produce something in the future. What, though, is the benefit for the original promise issuers? The advantage they gain is that it allows them to gain control of resources (including the work of others) so as to create something that they believe will have greater value in the future, either directly, such as a house paid for with a mortgage; or indirectly as a monetary profit for a firm. In this way money can assist human ingenuity in the making of more useful things out of less useful things. This might be, in the most simple case, just a matter of transporting some good from one group of people to another group that value it more; or in the more complex case, a cloth factory where workers spin cotton on machines. These different processes have two things in common. Firstly, they are creating new value; the pleasure the recipients of the transferred goods get from these goods did not previously exist and the cloth made in the factory is new. Secondly these processes take time. A ship takes time to transfer the existing goods; the factory takes time to make the cloth. These two facts together create a problem. Before the new value is created, there is nothing to exchange for it. The ship-owner has nothing to exchange with the original owners of the goods he transports; the factory owner has nothing to exchange with her workers whose labour is necessary for the production of the cloth. But by accepting promises to produce something valuable in the future and representing them with bank deposits, a bank can convert them into real value that can boot-strap the promised value into existence.

What Are the Drawbacks of Money?

The problems associated with money and a monetary economy are the flip side of the advantages. The best understood problem with money relates to its flexibility in exchanges over time. This problem is recognised largely thanks to John Maynard Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money of 1936. He pointed out that since the world is essentially unpredictable, and since money is durable and easy to store, there is a common tendency to accept it and then hold on to it even after the output promised in its issue has become available. The failure of this output to be sold means that the individual or firm that incurred a bank debt in issuing the money-creating promise becomes unable to repay their loan. This may result in bankruptcy of the individual or firm, with loss of jobs and further income. Banks lose interest income and if a bank is responsible for a number of such failed loans and loan write-offs then that bank may find that it runs out of capital, and the bank too risks failure. The anxiety and uncertainty associated with such events can be self-reinforcing, with the result that only some form of external intervention (usually by the government) can prevent further widespread business failures, unemployment and bank failures.

Problems are also caused by money’s anonymity and generality of value. Little thought is given to the significance of what it actually represents, both as it is created and as it is used in exchanges. We give no thought to the quality of the real promises that are issued in its creation. We are relying on the borrower’s and the bank’s self-interest to determine which promises are issued and which are not. Huge benefits or costs to other parts of society, to the environment or even to our future selves (so-called externalities) may play no part in their decisions. We can see the damage this has caused in the difficulties in tackling climate change, unhealthy life-styles and social problems.

Moreover, we fail to understand how money quantities relate to the real resources, goods and services for which they can be so easily exchanged. Most of the time we make no distinction between real wealth (real goods and services existing now) and money wealth (a claim on goods yet to be produced or marketed). While it may be appropriate for the individual to include money as part of his or her total wealth, it is most emphatically not correct for society as a whole. The significance of money for society as a whole is purely in terms of distribution. If you have more money than me, you don’t have more really existing wealth than I do, but you do have a bigger claim on future wealth than I do. This distinction is important because the pool of future wealth is much more difficult to expand than is the quantity of money. Consider the following scenario. Your neighbour earns £40,000 per year. You earn £20,000. The quantity of money expands and you end up earning £30,000 and your neighbour £65,000. On the face of it, you and your neighbour are both better off. In fact, if the pool of real wealth is unchanged, your neighbour’s claim on that pool started out as double that of yours and is now more than double. Your share of the pool has shrunk accordingly. Again, unless we examine the process that led to the expansion of the money supply, and unless we know whether the promises associated with it created real value for society as a whole that we can share in, then we don’t know what these changing monetary quantities mean. Without this knowledge, the poor lose the power to challenge the rich, resulting in widening inequality of real wealth both between and within countries.

Keynes’s insights into the time flexibility of money and how to tackle its consequences have (so far) helped to avoid a repeat of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Unfortunately we have up to now failed to address the other problems associated with money, so that human, environmental and social damage along with wealth inequality continue to increase unchecked.